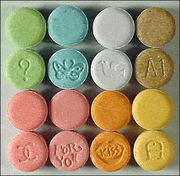

MDMA, which has been made criminally illegal worldwide, is taken most commonly in pill form.

Treatment with a pharmacological version of the drug ecstasy makes PSTD patients more receptive to psychotherapy, and contributes to lasting improvement. Norwegian researchers explain why.

People who have survived severe trauma – such as war, torture, disasters, or sexual assault – will often experience after-effects, in a condition called posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The symptoms can include anxiety, uncontrolled emotional reactions, nightmares, intrusive memories, sleep and concentration difficulties, evasion of situations that resemble the trauma, and feelings of shame or amnesia.

For many, the condition gradually goes away by itself. Other individuals experience PTSD as a chronic condition that needs treatment, which typically involves drugs that help with anxiety and depression, and/or psychotherapy.

More than just happy pills

Psychotherapy usually involves a combination of talk sessions and tasks. In exposure therapy, the focus is to help the patient digest the traumatic event in a safe context. So the patient realizes that the memories of the traumatic event and the situation surrounding it are not dangerous. The patient learns to deal with the traumatic incident as a painful memory, and not as if it will happen again.

“Studies show that exposure therapy can be a very effective treatment of post traumatic disorders. Yet far too many patients receive treatment only with drugs. But anxiety reducing drugs and anti-depressants may work against our efforts and reduce the patient’s emotional learning”, says PÃ¥l-Ørjan Johansen, a psychologist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Along with Teri Krebs, a neurobiologist at the university, he is now exploring what happens when chronic trauma patients are treated with a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacological versions of ecstasy, MDMA (3,4 methylenedioxy-N-methyl-amphetamine). A U.S. study, recently conducted by psychiatrist Michael Mithoefer, has shown remarkable success with this combination.

More open with ecstasy

Mithoefer took 21 people with chronic PTSD, all of whom had been subjected to documented abuse. All had also been through six months of treatment with traditional therapy, in addition to a three-month treatment with drugs. None, however, had shown any improvement from the treatment.

Under Mithoefer’s treatment, the patients stopped their usual anxiety-reducing drugs, and began a new treatment with twelve sessions of psychotherapy. During two of these therapy sessions, some patients were given doses of MDMA, while the others were given a placebo (a fake pill).

Two months after the treatment, 92 percent of MDMA patients had clinically significant improvement in their conditions: They were more open to therapy and were able to process the trauma. They managed to escape from their shells and shame, and to see lifelong patterns of behaviour. They were less dispirited, evasive and afraid. In contrast, only 25 percent of the patients in the placebo group showed progress. Everyone in this group was subsequently offered treatment with MDMA, and the results have been good, with no serious or lasting side effects.

Neuropsychological tests suggested that patients had improved mental ability after treatment. None of MDMA patients continued to take the drug after treatment. But many of them had managed to transform a crippling trauma into “only” a memory — a painful memory, but still more manageable than before.

Changes in brain activity

“This was a small study, and it must be followed up by more. But the results are promising, both in terms of safety and the effects of treatment. It is also important to stress that this is not about daily medication, but short-term, controlled use,” Johansen and Krebs say.

The Norwegian scientists have investigated both this and a number of other studies, and suggest the following explanation:

“For the first, MDMA contributes to increasing the level of oxytocin in the brain. This hormone stimulates emotions such as connection, proximity and trust. In a therapeutic context, it means that the patient may be better able to open up and have confidence in the therapist.

For the second, MDMA increases activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. This is an area in the anterior part of the brain that processes fear, lowers stress, and enables us to see events in perspective. This is where decisions are taken and feelings are regulated. Activity here is closely linked to activity in the amygdala, the area of the brain that is the centre for feeling fear. You could say that fear is formed in the amygdala, but is processed in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. While activity in the cortex is increased with MDMA, the drug simultaneously reduces activity in the amygdala. We believe this will help improve the regulation of emotions, allay fears and reduce evasive behaviours in a therapy situation.

For the third, MDMA triggers the ‘stress’ hormones noradrenalin and cortisol. These hormones are necessary to activate the emotional learning that leads to long-term reduction of fear.

In summary, we suggest that MDMA is an emotional enhancer that helps the patient feel safer and in control, better able to connect with memories, and more capable of the emotional processing that is needed for improvement.”

International research

MDMA clinical studies are being undertaken in many countries, both in people and animals. Krebs and Johansen have now received funding from the Research Council of Norway to pursue these results.

The research will be conducted both in Norway (at Institute of Neuroscience, NTNU) and at the Harvard Medical School in the U.S., where a similar study on the treatment of anxiety disorders is underway. But the Research Council of Norway would also like to help the two to build Norwegian expertise in this field, so that large clinical studies can be undertaken in Norway.

Source: Norwegian Institute of Science and Technology via Alpha Galileo Teri Krebs’ and PÃ¥l-Ørjan Johansen’s explanatory model is being published in the “Journal of Psychopharmacology”.