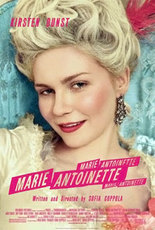

Marie Antoinette, a 2006 movie about the French Revolution, is one of nine historical movies with factual errors included in a study of how such films influence student retention of history lessons

The study, forthcoming in the journal Psychological Science, suggests that showing popular history movies in a classroom setting can be a double-edged sword when it comes to helping students learn and retain factual information in associated textbooks.

“We found that when information in the film was consistent with information in the text, watching the film clips increased correct recall by about 50 percent relative to reading the text alone,” explains Andrew Butler, a psychology doctoral student in Arts & Sciences.

“In contrast, when information in the film directly contradicted the text, people often falsely recalled the misinformation portrayed in the film, sometimes as much as 50 percent of the time.”

For a slide show detailing inaccuracies in the nine Hollywood films used in the study, visit: http://news-info.wustl.edu/tips/page/normal/14418.html.

Butler, whose research focuses on how cognitive psychology can be applied to enhance educational practice, notes that teachers can guard against the adverse impact of movies that play fast and loose with historical fact, although a general admonition may not be sufficient.

“The misleading effect occurred even when people were reminded of the potentially inaccurate nature of popular films right before viewing the film,” Butler says. “However, the effect was completely negated when a specific warning about the particular inaccuracy was provided before the film.”

Butler conducted the study with colleagues in the Department of Psychology’s Memory Lab. Co-authors include fellow doctoral student Franklin M. Zaromb, postdoctoral researcher Keith B. Lyle and Henry L. “Roddy” Roediger III, the Lab’s principal investigator and the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of Psychology.

“These results have implications for the common educational practice of using popular films as an instructional aid,” Butler concludes.

“Although films may increase learning and interest in the classroom, educators should be aware that students might learn inaccurate information, too, even if the correct information has been presented in a text. More broadly, these same positive and negative effects apply to the consumption of popular history films by the general public.”

Source:Washington University in St. Louis