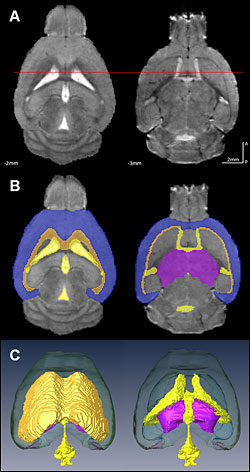

The scientists used MRI data mapped onto an existing atlas of the mouse brain to compare the effects of drinking ethanol and water on brain volume overall and region-by-region in mice with and without dopamine D2 receptors. Alcohol-drinking mice that lacked dopamine receptors had lower overall brain volume and reduced volume in the cerebral cortex (blue) and thalamus (purple) compared with D2 receptor-deficient mice drinking water. Alcohol-drinking mice with dopamine receptors did not show these deficits in response to drinking alcohol, suggesting that dopamine receptors may be protective against the brain atrophy associated with chronic drinking.

“This study clearly demonstrates the interplay of genetic and environmental factors in determining the damaging effects of alcohol on the brain, and builds upon our previous findings suggesting a protective role of dopamine D2 receptors against alcohol’s addictive effects,” said study author Foteini Delis, a neuroanatomist with the Behavioral Neuropharmacology and Neuroimaging Lab at Brookhaven, which is funded through the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Coauthor and Brookhaven/NIAA neuroscientist Peter Thanos stated that, “These studies should help us better understand the role of genetic variability in alcoholism and alcohol-induced brain damage in people, and point the way to more effective prevention and treatment strategies.”

The current study specifically explored how alcohol consumption affects brain volume — overall and region-by-region — in normal mice and a strain of mice that lack the gene for dopamine D2 receptors. Half of each group drank plain water while the other half drank a 20 percent ethanol solution for six months. Then scientists performed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans on all the mice and compared the scans of those drinking alcohol with those from the water drinkers in each group.

The scans showed that chronic alcohol drinking induced significant overall brain atrophy and specific shrinkage of the cerebral cortex and thalamus in the mice that lacked dopamine D2 receptors, but not in mice with normal receptor levels. Mice in both groups drank the same amount of alcohol.

“This pattern of brain damage mimics a unique aspect of brain pathology observed in human alcoholics, so this research extends the validity of using these mice as a model for studying human alcoholism,” Thanos said.

In humans, these brain regions are critically important for processing speech, sensory information, and motor signals, and for forming long-term memories. So this research helps explain why alcohol damage can be so widespread and detrimental.

“The fact that only mice that lacked dopamine D2 receptors experienced brain damage in this study suggests that DRD2 may be protective against brain atrophy from chronic alcohol exposure,” Thanos said. “Conversely, the findings imply that lower-than-normal levels of DRD2 may make individuals more vulnerable to the damaging effects of alcohol.”

That would in effect deal people with low DRD2 levels a double whammy of alcohol vulnerability: Previous studies conducted by Thanos and collaborators suggest that individuals with low DRD2 levels may be more susceptible to alcohol’s addictive effects.

“The increased addictive liability and the potentially devastating increased susceptibility to alcohol toxicity resulting from low DRD2 levels make it clear that the dopamine system is an important target for further research in the search for better understanding and treatment of alcoholism,” Thanos said.

Source:The above story is reprinted from materials provided by DOE/Brookhaven National Laboratory