Popular media’s hypersexualization of women may be worse than you think

A study by University at Buffalo sociologists has found that the portrayal of women in the popular media over the last several decades has become increasingly sexualized, even “pornified.” The same is not true of the portrayal of men.

These findings may be cause for concern, the researchers say, because previous research has found sexualized images of women to have far-reaching negative consequences for both men and women.

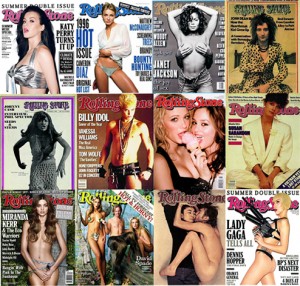

Erin Hatton, PhD, and Mary Nell Trautner, PhD, assistant professors in the UB Department of Sociology, are the authors of “Equal Opportunity Objectification? The Sexualization of Men and Women on the Cover of Rolling Stone,” which examines the covers of Rolling Stone magazine from 1967 to 2009 to measure changes in the sexualization of men and women in popular media over time.

The study will be published in the September issue of the journal Sexuality & Culture

UB sociologists Erin Hatton and Mary Nell Trautner are the authors of "Equal Opportunity Objectification?," which examines 43 years of Rolling Stone magazine

After analyzing more than 1,000 images of men and women on Rolling Stone covers over the course of 43 years, the authors came to several conclusions. First, representations of both women and men have indeed become more sexualized over time; and, second, women continue to be more frequently sexualized than men. Their most striking finding, however, was the change in how intensely sexualized images of women — but not men — have become.

In order to measure the intensity of sexualized representations men and women, the authors developed a “scale of sexualization.” An image was given “points” for being sexualized if, for example, the subject’s lips were parted or his/her tongue was showing, the subject was only partially clad or naked, or the text describing the subject used explicitly sexual language.

Based on this scale, the authors identified three categories of images: a) those that were, for the most part, not sexualized (i.e., scoring 0-4 points on the scale), b) those that were sexualized (5-10 points), and c) those that were so intensely sexualized that the authors labeled them “hypersexualized” (11-23 points).

In the 1960s they found that 11 percent of men and 44 percent of women on the covers of Rolling Stone were sexualized. In the 2000s, 17 percent of men were sexualized (an increase of 55 percent from the 1960s), and 83 percent of women were sexualized (an increase of 89 percent). Among those images that were sexualized, 2 percent of men and 61 percent of women were hypersexualized. “In the 2000s,” Hatton says, “there were 10 times more hypersexualized images of women than men, and 11 times more non-sexualized images of men than of women.”

“What we conclude from this is that popular media outlets such as Rolling Stone are not depicting women as sexy musicians or actors; they are depicting women musicians and actors as ready and available for sex. This is problematic,” Hatton says, “because it indicates a decisive narrowing of media representations of women.

“We don’t necessarily think it’s problematic for women to be portrayed as ‘sexy.’ But we do think it is problematic when nearly all images of women depict them not simply as ‘sexy women’ but as passive objects for someone else’s sexual pleasure.”

These findings are important, the authors say, because a plethora of research has found such images to have a range of negative consequences:

“Sexualized portrayals of women have been found to legitimize or exacerbate violence against women and girls, as well as sexual harassment and anti-women attitudes among men and boys,” Hatton says. “Such images also have been shown to increase rates of body dissatisfaction and/or eating disorders among men, women and girls; and they have even been shown to decrease sexual satisfaction among both men and women.”

“For these reasons,” says Hatton, “we find the frequency of sexualized images of women in popular media, combined with the extreme intensity of their sexualization, to be cause for concern.”

Hatton is the author of “The Temp Economy: From Kelly Girls to Permatemps in Postwar America” (Temple University Press, 2011). Her work focuses on the sociology of work, with attention to gender, race, labor, political economy and public policy.

Trautner has published articles in journals such as the American Sociological Review, Gender & Society, and Sociology of Crime, Law and Deviance. Her work examines how law, culture and organizational practices shape how inequality is created, perpetuated and/or experienced.

Source: University of Buffalo